Community attitudes on mine rehabilitation of open-cut coal mines in regional New South Wales

by Karin Fogarty MAusIMM, with Marit Kragt and Benedict White

A version of this article was originally published and presented at AusIMM’s 2021 Life of Mine Conference. AusIMM members can access the full conference proceedings through the Digital Library.

The mining industry's contribution to regional economies is undeniable.

At the same time, mining often introduces environmental and social impacts directly felt by surrounding communities. In addition to being a compliance obligation, mine rehabilitation is carried out to minimise such impacts and, more recently, seen as a way to demonstrate a mining company’s social performance. It is widely accepted that community engagement on mine rehabilitation outcomes is needed to ensure acceptance and successful transition to post-mining land uses (PMLU) (Everingham et al., 2018; Owen and Kemp, 2018). Whilst the community's role in a mine operation's rehabilitation and closure outcomes is acknowledged, in New South Wales there appears to be little research on community perceptions towards mine rehabilitation.

In Australia, there is a perception that mining negatively affects the environment and local communities (Moffat et al., 2017). Awareness and concern held by the community about the environment, as well as socio-economic interests in what happens after mining, has arguably never been greater. Consequently, mine site rehabilitation is required to be ever more effective and have outcomes in keeping with the community's aims and aspirations. Current public expectations are that mine sites will be rehabilitated (Lamb et al., 2015); that it is important to do so (Moffat et al., 2017); and that in situ mine site rehabilitation is preferred over compensatory biodiversity offset programs (Burton et al., 2012).

Communities are typically engaged about mine rehabilitation and closure aspects throughout the mine life via company community engagement programs and the regulatory approval process. Despite this level of community engagement, negotiations between mining companies and regulators ultimately agree on the condition of mine closure and rehabilitation. Therefore, whilst it is recognised that community plays a role in a mine operation’s rehabilitation and closure outcomes, there is limited information about the public’s preferences towards mine site rehabilitation and PMLU. We present a study to address this knowledge gap for a case study in regional NSW.

Methods

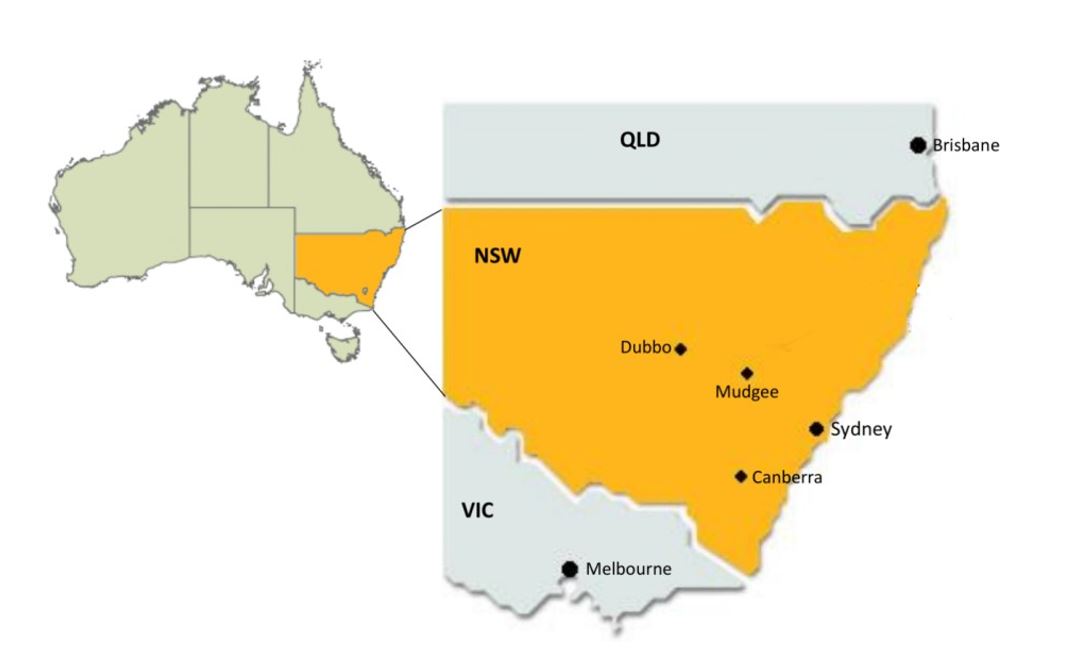

Three focus groups were held over three separate days in July 2019 in regional NSW (Figure 1) with a total of 29 attendees. Focus groups in Dubbo and Mudgee were attended by local community members. A second focus group in Mudgee included community members who have technical knowledge or an interest in mining, including some defined stakeholders of a local coal mine. Thematic analysis was undertaken of the data to identify emergent themes.

Figure 1. Location of Mudgee and Dubbo in NSW, Australia.

Results

Four main themes were discussed in the workshops addressing attendees’ opinions about: 1) mine rehabilitation (general); 2) mine rehabilitation (success and benefits of achieving); 3) decision making; and 4) post-mining land uses. Points of discussion were analysed to identify the emergent themes and are presented in Figure 2.

Across all workshops, participants actively discussed their thoughts on mine rehabilitation. Results indicate that while residents recognise the economic contribution of coal mining to the region, they are concerned that mine rehabilitation decisions are not sufficiently transparent. A tone of distrust of mining companies was evident, with participants believing there is a lack of transparency on the actual plan, the standard of rehabilitation and the PMLU.

Participants commonly expressed scepticism about a mining company's ability to achieve rehabilitation goals. However, this appeared to be predominately directed at their ability to reinstate previous native ecosystems rather than to create alternative land uses.

There was no consistent response regarding the definition of rehabilitation. Some participants emphasised the physical and ecological aspects, while others suggested this should be expanded to include the rehabilitation's usefulness to future generations and local community. Some thought the engagement process should also be specified around mine rehabilitation.

While all participants appeared to agree that rehabilitation is important to complete, some believed rehabilitation occurs because of recent regulatory changes and environmental and community advocacy pressure, and not because mining companies want to do the right thing. Broadly speaking, participants believed the industry has made concerted improvements regarding mine rehabilitation and is currently performing well.

The ultimate goal identified across all focus groups was seeing rehabilitation evolve to produce beneficial land uses that provide employment, that are not an economic burden on the community and that are useful to the community. Successful mine rehabilitation was often defined in terms of aesthetics, although it was acknowledged this is difficult to quantify. It was also generally agreed that rehabilitation will take a long time; however, this is largely accepted as long as it commences as soon as possible.

Figure 2. Identified emergent themes.

The sustainability of the PMLU was identified as a success indicator by participants. It should be measured to show how future generations directly benefit from rehabilitated land or reduce human impacts of future developments by avoiding disturbing other areas. Others suggested that a PMLU proposing alternative energy such as solar or wind farms could also be seen as a sustainable outcome for society.

Information needed for community members to assist in decision making was broad and varied. Trade-offs of the identified aspects were common for participants and ultimately, as long as the perceived benefits outweigh the costs of rehabilitation, generally influenced their standpoint. It was deemed the community should have the strongest say in what happens after a mine closes, although it was felt this is not the current case with the community having to inherit the outcome rather than be part of the process.

While it was generally preferred to reinstate the land use before mining, it was conceded by some this might not be practical and therefore prefer an alternative land-use that derives an income to at least pay for on-going land management. Participants identified that mined lands could be used for a range of potential PMLUs, including renewable energy generation and providing recreational opportunities.

Acknowledgements

Karin Fogarty is a recipient of the AusIMM EEF PhD scholarship.

Dr Marit Kragt is funded by the Australian Government as an Australian Research Council Discover Early Career Award (DE160101306) and received UWA Fellowship support.

References

Burton, M, Zahedi, S and White, B, 2012. Public preferences for timeliness and quality of mine site rehabilitation. The case of bauxite mining in Western Australia, Resources Policy, 37:1-9.

Everingham, J, Rolfe, J, Lechner, A and Kinnear, S, 2018. A proposal for engaging a stakeholder panel in planning post- mining land uses in Australia’s coal rich tropical savannahs, Land Use Policy, 79:397–406.

Lamb, D, Erskine, P and Fletcher, A, 2015. Widening gap between expectations and practice in Australian minesite rehabilitation, Ecological Management and Restoration, 16 (3):186-195.

Moffat, K, Pert, P, McCrea, R, Boughen, N, Rodriguez, M and Lacey, J, 2017. Australian attitudes toward mining: Citizen Survey – 2017 Results. EP178434. (CSIRO: Australia).

Owen, J and Kemp, D, 2018. Mine closure and social performance: an industry discussion paper. (Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, Sustainable Minerals Institute, The University of Queensland: Brisbane).