In support of frontline mining leaders

Frontline leaders play a critical role in the safe and productive operations of Australia’s mining, resources and heavy industries.

These leaders set the workplace culture, especially during night shifts and weekends, by providing team direction and encouragement, providing access to resources, fulfilling statutory requirements, enacting and reinforcing risk management systems, setting the standards on shift and acting as the primary conduit of communications between senior leaders and team members.

This article examines the current and future roles of frontline leaders through the lens of technical capabilities and leadership styles required. The article then explores how requisite changes may occur, the support needed from employers and industry, and particular challenges to be navigated.

The role of the frontline leader is changing, and the pace of change is accelerating. The skills that have been successful in the past are proving useful but not sufficient for the present and will be further challenged in the future. The traditional role of the frontline leader with emphasis on operational delivery remains very much in existence and it is clearly important; however, the ‘command and control’ leadership style is proving limiting and may in fact be a barrier to important improvements required in safety outcomes and productivity.

As the mining industry evolves in the face of strong trends to be more inclusive, more transparent and responsive, integrating new technologies, remote operations and other workplace trends, it is instructive to review what capabilities are required in our frontline leaders to deliver these improvements.

To answer this, it is useful to see these transitioning leadership roles through two dimensions. Firstly, the technical capabilities required of frontline leaders (the ‘what’) and secondly, the social capabilities and leadership style (the ‘how’).

Technical capabilities

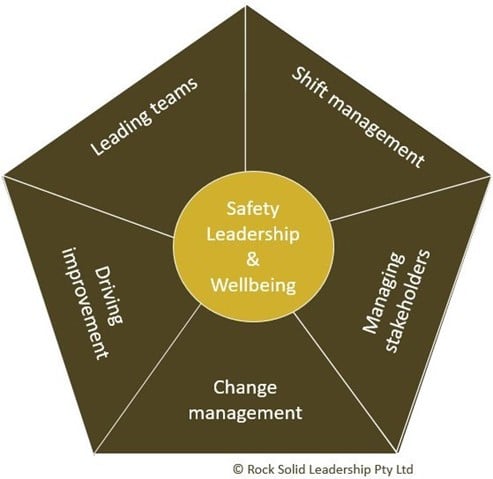

Figure 1 illustrates a model the author has used to understand the technical capabilities required.

- Safety leadership and wellbeing: At the core of any frontline leader role is the safety and care for their crew and others in their workplace.

- Shift management: Confident, disciplined application of systems and tools to drive safe production and engagement.

- Leading teams: Understanding the role of the leader in a functioning team, how their style interacts with team members, how to engage and motivate others.

- Managing stakeholders: How to engage with third parties, clients and contractors to ensure safe and positive outcomes.

- Driving improvement: Working with team members in a disciplined manner to improve operations and safe outcomes by bringing useful improvement tools and harnessing the combined input of the team.

- Change management: Confident leading teams through change with good processes and sensitive engagement.

Figure 1. Technical capabilities required in frontline leaders.

Leadership styles

Of course, being capable will not suffice and the second dimension examines leadership styles. Leaders that embrace a self-awareness of personal style, and understand the importance of being authentic and engaging with an ability to adapt style to meet the situation, will better meet emerging workplace requirements. Style flexibility is paramount; leaders need to be confident in operating across the spectrum from directive styles to a more coaching style of leadership. The transition from directive leadership styles to coaching styles will be fundamental to tapping into the considerable improvement capabilities in our teams, thereby improving engagement, improving retention and delivering positive safety and production outcomes.

In addition, this style flexibility will assist our leaders in dealing with the so-called Authenticity Paradox, as they find themselves at the fulcrum of management instructions and crew engagement. This manifests itself at times through being instructed to implement the policies and standards of their employer, with knowledge that this may challenge crew engagement, productivity and safety outcomes.

Supporting frontline leaders

It is instructive to ask leaders how they understand their role responsibilities today, and for the future, and how employers have assisted them to develop the capabilities and skills required. In the author’s experience role clarity and support for development varies widely. Employees are often well trained for their initial roles in industry, then step up into leadership roles with little formal leadership development and mixed levels of support.

Frontline leaders in mining and resources typically come from a relatively narrow range of backgrounds: capable and respected operators and tradespersons who are willingly promoted to a leadership role; professionals who seek leadership experience enroute for more senior roles; and leaders who are invited to step up to fill a vacancy temporarily that becomes a formal/informal permanent leadership role. The industry is changing and encountering a broadening of the pools of talent with more diverse candidates achieving leadership roles and this must continue. However, the pools of talent for new frontline leaders are relatively shallow and the change in leadership style described above must come from within.

So how do we support our frontline leaders for this transition and how are employers developing their frontline leaders for the emerging role requirements?

It is instructive to consider this through a change management lens, in this case the ADKAR tool, for the frontline leader.

- Awareness: How aware are leaders of their leadership style and its impact upon others? Are they conscious of additional styles that might improve outcomes?

- Desire: What is the compelling reason to change? Is the risk of amending personal leadership styles manageable, sustainable, personally desirable and supported by my leader?

- Knowledge: Where can the leader efficiently and effectively develop an understanding of existing skills, emerging capability requirements and close What is the access to on-the- job learning, on-site or off-site education and e-learning and what is its suitability? Is it tailored for the individual’s needs or more generic in approach?

- Action: Post a program of skills learning, is there a personal program for change, that will allow practicing and embedding new skills and actioning in the workplace?

- Reinforcement: How do the new skills become habits, how are they rewarded, is the environment supportive, are systems aligned?

Where are the weaknesses in this program of change? Arguably two areas stand out, creating a compelling reason to change and embedding the change into working habits within a supportive work environment. These two aspects need particular attention.

A supportive environment needs several important elements; commitment and communication from more senior levels in the organisation outlining the ‘why’; a timely one-on-one discussion with their immediate leader on expectations for the program and afterwards; relevant and tailored program delivery; follow on with leadership on a small number of actions and resources needed; and a focused period to embed the agreed actions.

Embedding personal actions remains challenging. Coaching will play an important role, both to role model the desired behaviours and to gain commitment for change. Ideally the coach will be an immediate leader or peer providing support, time and attention. Practically this is challenged by the nature of work design, and the existing skills of senior leaders. Focused attention from a dedicated external coach can be a useful approach to embed learnings and new skills. Developing habits takes time, and periodic coaching interventions over three months is likely necessary to form new habits.

In closing, the role of the frontline leader is changing, and this should be embraced as it offers a pathway to lift safety and operational performance. Complementing existing leaders’ skills and capabilities is important and will require careful planning, execution, close follow-up and reinforcement.

A version of this article was originally published as a paper in the 2022 Minesafe International Conference Proceedings. Members can access the full conference proceedings via the Digital Library here.