JORC Code 2024 – Modifying Factors, including ESG and Risk

JORC Code 2024 Update

The long-awaited Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC) Code update Exposure Draft (JORC, 2024a) and draft Guidance Notes (JORC, 2024b), the result of prodigious review and discussion by the Committee and many contributors, is available for public comment until 31 October 2024. An evolution on JORC 2012, the updated draft modernises the disclosure requirements for Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) considerations as classes of ‘Modifying Factors’. This integration of contemporary ‘ESG’ expectations is bolstered by the inclusion of risk assessments (analysing the consequences and uncertainty of opportunities and threats). The Exposure Draft Code responds to the greatly increased standards of transparency expected of the minerals industry by the financial sector, regulators and the public. In this light, it is important to revisit and consider the ‘why’, ‘what’ and ‘how’ of the JORC Code, in line with its core principles of Transparency, Materiality, and Competence.

Why: Transparency

The purpose of the Code – disclosure, not prescription

Many geologists, particularly those at the innovative and junior end of the sector, ask “why do we even need the JORC Code?”. They appear to misunderstand its purpose, believing it to be a form of regulatory compliance. While ASX/NZSX and ASIC can enforce compliance on companies, the JORC cannot. Rather, the JORC Code’s purpose is to make public relevant and material information in support of an open contestable market in mineral assets and properties. This is to the benefit of all who seek to work competitively within the minerals industry. In essence, an informed (minerals property) market is a ‘good market’ (Fama, 1970).

Whilst the form and function of the JORC Code has evolved, its principles and public reporting purpose are unchanged. The Code is principally a disclosure standard, not a performance standard. Its purpose is to provide a framework to standardise the reporting of ‘what’ is known or unknown, and ‘how’ relevant analyses and assessments have been undertaken.

Caveat emptor (‘let the buyer beware’) and knowledge symmetry are the key enablers of an effective market. In this regard, performance and disclosure represent two sides of the same coin – public claims absent of verifiable assumptions or demonstrated performance are deceptive. The JORC Code is about material disclosures, whereas it is ASX/NZSX and ASIC that oversee compliance.

Is there a clear and realistic pathway to project delivery?

Principally, the Code is in place to enable users (investors, regulators and the public) to understand and assess ‘where is this project in the development trajectory, and what needs to be true for it to proceed?’ Critically, the Code specifies that disclosures should be project specific, covering all relevant and reasonably available information at the time of reporting.

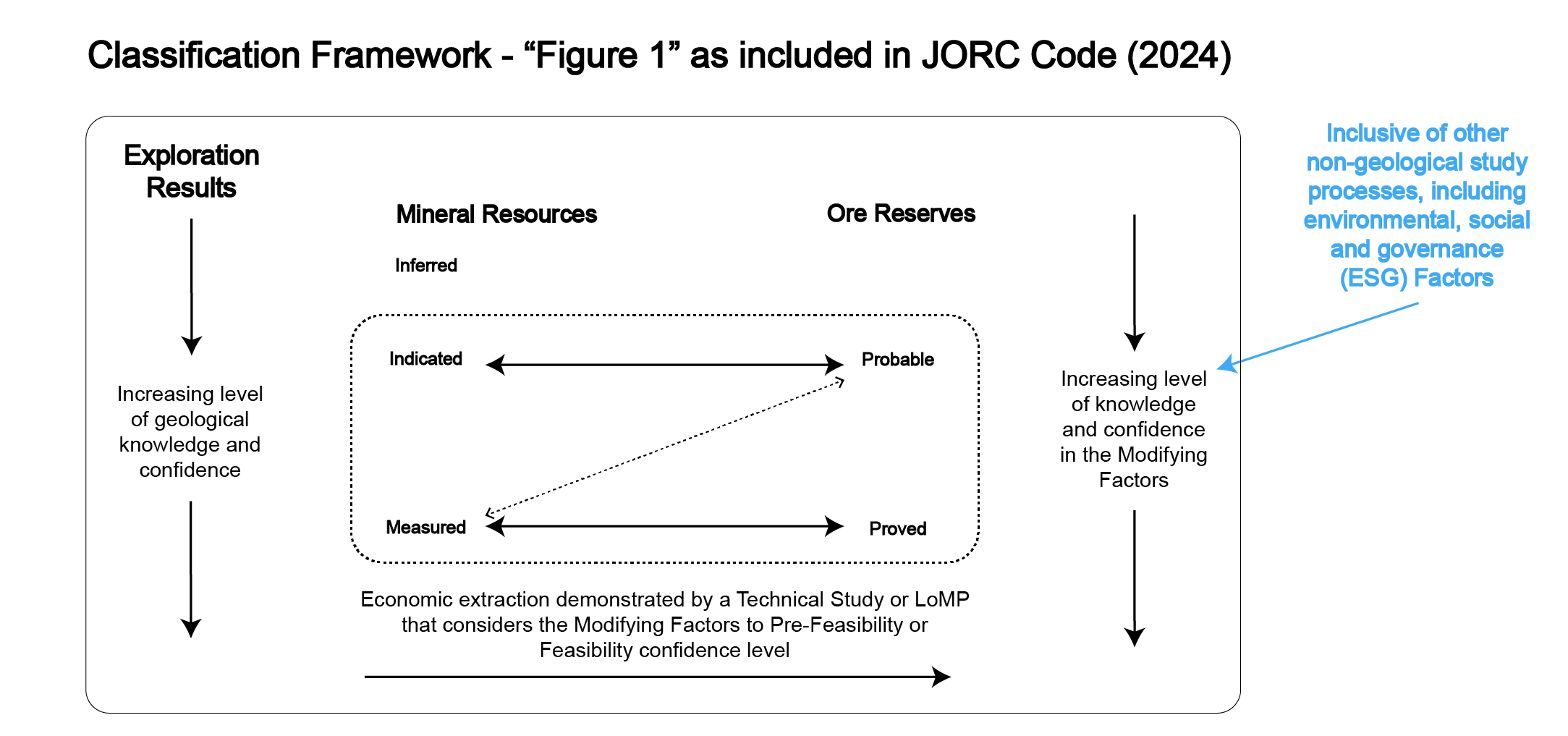

This is made clear in the relationship between Indicated and Measured Mineral Resources and Probable and Proved Ore Reserves defined in the Code (Figure 1). At their starkest, Mineral Resources are primarily geological and with greater definition drilling can move from Probable to Proved. Ore Reserves can have the same geological parameters but also require accompanying non-geological studies that describe Modifying Factors along a confidence continuum to the point of making the Reserves economically extractable with all reasonable and material things considered.

Figure 1: Mineral Resources/Ore Reserves (adapted from The JORC Code Exposure Draft)

What: Materiality

ESG guidance provisions

In the 2024 JORC Code Exposure Draft, ESG matters are explicitly included in the suite of possible ‘Modifying Factors’. Clause 4.7 states:

‘Modifying Factors’ are considerations used to assess and estimate Exploration Targets, Mineral Resources, and/or Ore Reserves. Modifying Factors include, but are not restricted to mining, processing, metallurgical, infrastructure, economic, marketing, legal, environmental, social and governance (ESG) and regulatory factors.

ESG-related matters are long-standing JORC Modifying Factors, albeit with only skeletal mention in the JORC Code 2012. The 2024 evolution amplifies their importance, along with nuanced changes such as the superseding of ‘government’ into separate ‘governance’ and ‘regulatory’ categories. This change is pragmatic, expanding regulatory matters (tenure, permitting and approvals compliance) to cover company managerial governance aspects. The amplification of ESG matters is apparent in clauses 4.8 and 4.9:

The effects of Modifying Factor variability on the reasonable prospects for economic extraction of a Mineral Resource, or on the likely economic viability and/or on the estimation and classification of an Ore Reserve, must be disclosed and discussed.

Critically ESG factors must be given equal prominence to other Modifying Factors. This requirement acknowledges the nature of evolving knowledge of ESG-related matters and requires that the available and material knowledge at any reporting stage is needed in the Public Report.

Importantly, JORC Code users should note that ESG-related project disclosure and Sustainability Reports (or equivalent) serve different purposes and audiences.

Reasonable Prospects for Eventual Economic Extraction: theory vs practice

Albert Einstein is quoted as having said “In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not”. This adage is amply demonstrated in the recent history of minerals projects, where there have been liberties around assumptions in theory that have greatly affected development horizons. In this respect, the updated Code revisits the principle of Reasonable Prospects of Economic Extraction (RPEE), dropping the word ‘eventual’ as being implicit and redundant. The word ‘eventual’ in JORC 2012 allowed for a myriad of theoretical or untested assumptions to be tolerated. In practice, in a world demanding economic rigour, such assumptions cannot be tolerated. As projects move along a development trajectory to published Reserve status, assumptions must make way to data-driven and competency-based assessments in line with the demands of modern finance and actuarial insurance.

Does a disclosure pass the ‘pub test’?

In the early stages of a project when there is a paucity of data, before the investors, lenders and the insurers turn up, proponents need to be continually asking themselves ‘what needs to be true for assumptions to become certainties?’. While every orebody and its context is unique, needing to be analysed from a bottom-up perspective, there are now well-understood common ESG-related dimensions that should be tested. The most frequently referenced economic and ESG-related issues feature in AusIMM’s Professional Certificate in ESG and Social Responsibility online course (AusIMM, 2024a) (refer to Figure 2), adapted from a meta-study of 150 investment due diligence instruments (Sauvant and Mann, 2019). When any of these are not relevant in context, they can and should be stated as not applicable on an ‘if not, why not’ basis.

Figure 2: Economic and ESG (EESG) Elements Relevant to the Minerals Sector

If not, why not

Materiality, transparency and competency remain core principles of the Code and should drive analysis and assessment. Consistent with the (E)ESG themes set out in Figure 2, the JORC Code Exposure Draft and accompanying Guidance include ESG tables that serve to prompt project proponents on common “outbound” external impacts (risks to stakeholders) and “rebounding” risks to the project that they should be managing, and to prompt financiers and insurers on what questions they should be asking. The Code’s important principle of ‘if not, why not’ fortifies this process. The Guidance tables are ‘lean’ and not a ‘what to do’ guide. In practice, competent ESG practitioners and managers should undertake assessments that ensure disclosures are ‘fit for purpose’ and ‘fit for context’. This is essential to demonstrate that proponents are sufficiently de-risking their projects so they do not fall into the 30–40% that fail to progress due to Modifying Factors associated with ‘above ground issues’ (Davis and Franks, 2014). This statistic has been laid bare by a recent S&P Global report (Bonakdarpour et al., 2024), which found only three mining projects have been developed and reached full operations in the USA since 2002.

Risk management preconditions: what needs to be true by when?

The Exposure Draft Code also strengthens the requirement for analysing and disclosing risk, defined as “The effect of uncertainty on Exploration Targets, Mineral Resources, and Ore Reserves and comprises Opportunities and Threats”, with a requirement that Competent Persons consider all identified risks in preparing a Public Report. From an ESG perspective, the emphasis on uncertainty, and its disclosure, is an important improvement. Arguably, the greatest locus of uncertainty at a minerals project is often in the world external to the controlled internal technical domains; in essence, the world controlled by others. Reduction in variation is the aspiration and outcome of all proactive management, hence consistent ESG risk analysis, threat mitigation and opportunity enhancement provide for integrated and tight management and improved chances of a minerals project progressing to become a profitable operating asset.

How: Competence

Competent persons and specialists

The Exposure Draft JORC Code emphasises the role of ‘Competent Persons’ in signing off Public Reports, a requirement prominent in the Code since its original promulgation in 1972. New requirements include the need for the Competent Person to have a ‘CV of Record’ lodged on the JORC website, and to use ‘Specialists’ for areas of analysis that lie beyond their expertise. Specialists must also be able to verify their relevant competencies. The requirement for Specialist sign-off recognises the increasingly complex nature of work required to advance minerals projects and, along with other discipline areas, greatly enhancing the need to get beyond “guess work” for ESG-related analysis and disclosure. In fact, advanced project (declared Ore Reserves) analysis, management and disclosure is now only possible with a multi-disciplinary team-based approach. This in turn requires Competent Persons to have an ability to manage teams of specialists and pull their work together in a risk-based, balanced and coherent way – in effect, a new competency requirement.

The complexity and multi-factor nature of resource development risk challenges the notion of a ‘single source of truth’. While the updated Code recognises that Competent Persons need to oversee a process that analyses, assesses and balances the direct, indirect and cumulative (net) impacts of Modifying Factors in Resource and Reserve statements, the new competency requirement for managing multidisciplinary teams, options analysis and assessment needs elucidating in the Code.

Standards and Guidelines

When it comes to ESG matters, the updated Exposure Draft provides expanded guidance on minerals project external impacts, reciprocating risks to the project and the adequate disclosure of both. It balances description with digestibility, the latter being important – advice is only as effective as a reader’s ability to take it in and understand it. In this regard, the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum (CIM) Environmental, Social and Governance Guidelines for Mineral Resource and Mineral Reserve Estimation (CIM, 2023) are expansive and serve a different purpose to the JORC Code. By setting out detailed advice tailored for E, S and G practitioners, specialists and managers, the CIM Guideline’s 64 pages are a valuable complement to JORC and similar code reporting. Although written from a Canadian perspective, the CIM Guidelines are comprehensive and globally applicable, hence JORC and other minerals reporting bodies need not replicate them and add to the ESG advisory fog.

Another valuably coincident publication is AusIMM’s Study Processes Handbook (AusIMM, 2024b), setting out in 190 pages everything that studies managers should be doing to build a comprehensive knowledge base for minerals project decision-making, design and execution. Permitting, environmental and social aspects are covered in Chapter 2. There is tight coherence between the Study Processes Handbook, the Exposure Draft JORC Code, and the CIM Guidelines, demonstrating there is established science in ESG.

Conclusion: Apples with apples

Although not emphasised in the Exposure Draft, the update is more than a geological assessment with Modifying Factors on the side. Essentially, it sets out to identify ‘what is economic’ or ‘left remaining’ of a geological resource after reasonable and justifiable assumptions around Modifying Factors are applied. Approached properly, this can prevent unwise expenditure on projects that have no clear pathway to consent and permitting.

The proposed updated Code is, in effect, a comprehensive minerals project disclosure guide. ‘Why’ the JORC Code is needed has long been beyond question, and the changes in the principles of the proposed updated Code are negligible, not fundamental. From an ESG perspective, the ‘What’ is now increasingly defined and laid out in varying detail in coherent and consistent guidance materials generated by the AusIMM and the CIM. ‘How’ the Code should be used is still being discussed, debated and refined, and will only be discovered through execution and operational practice in the years ahead. This ‘How’ should reveal the execution risk that investors and other stakeholders, such as governments, insurers and affected people, need to know to inform their decision making. The proposed updated JORC Code provides the architecture, ‘recipe’ and language to demystify decision making by standardising the Public Reporting of resource projects. In short, it enables apples with apples comparisons.

Overall, the proposed updated Code is a great improvement on JORC 2012. It has vastly better structure and is more coherent with balanced accompanying Tables and Guidelines offering refined guidance to minerals explorers and the industry overall. It brings great credit to the volunteers who applied their time and expertise to produce it.

References

AusIMM (2024a). Professional Certificate in ESG and Social Responsibility online course

https://www.ausimm.com/courses/professional-certificates/esg-and-social-responsibility-1

AusIMM (2024b). Study Processes Handbook. Monograph 35. https://www.ausimm.com/publications/monograph/monograph-35---study-processes-handbook/

Bonakdarpour, M, Hoffman, F and Rajan, K (2024). Mine Development Times: The US in perspective. S&P Gobal. https://cdn.ihsmarkit.com/www/pdf/0724/SPGlobal_NMA_DevelopmentTimesUSinPerspective_June_2024.pdf

CIM (2023). CIM Environmental, Social and Governance Guidelines for Mineral Resource and Mineral Reserve Estimation.

https://mrmr.cim.org/media/1169/cim-esg-guidelines-for-mineral-resource-and-mineral-reserve-estimation.pdf

Davis, R and Franks, D (2014). Cost of company-community conflict in the extractive sector. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Report No. 66. Harvard Kennedy School: Cambridge, MA.

https://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/media/docs/603/Costs_of_Conflict_Davis-Franks.pdf

Fama, E F (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work, Vol. 25. No.2. The Journal of Finance. Wiley

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2325486

JORC (2024a). The JORC Code Exposure Draft. August 2024

https://www.jorc.org/code-update/

JORC (2024b) The JORC Code Exposure Draft Guidance Notes. August 2024

https://jorc.org/docs/Draft_JORC_Guidance_Note_01Aug2024_readonly.pdf

Sauvant, K P and Mann, H (2019). Making FDI more sustainable: Towards an indicative list of FDI sustainability characteristics. The Journal of World Investment & Trade; Publication Date 17 Dec 2019. https://brill.com/view/journals/jwit/20/6/article-p916_6.xml?language=en.