The past and future of global minerals demand

This article is based on a webinar delivered to the AusIMM Metallurgical Society in March 2024.

The global demand for minerals has long been known to be characterised by periods of high demand followed by periods of low demand.

These are often referred to as cycles. There are cycles of short (multi-year) duration and cycles of long (multi-decade) duration. In this article I will seek to explain the driving forces behind the long duration cycles.

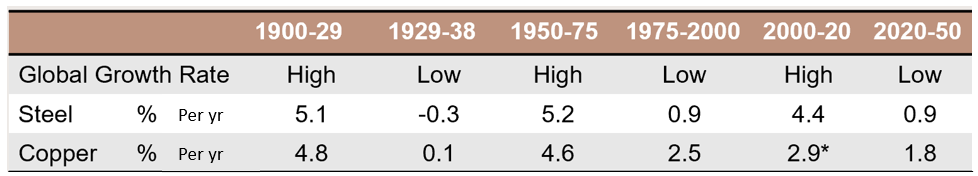

There have been five such cycles since 1900. Four of them were in the 20th century, and the fifth was the first 20 years of this century, much of which was dominated by the China mining boom. Table 1 shows the time period for each of them, and also shows the average annual rate of demand growth for both steel and copper metal during each cycle. I will discuss the outlook for demand to 2050 later in this article, and this forecast demand growth is also shown.

The figures used in the table are for metal produced from global mine production. Copper data was taken from the US Geological Survey, while steel data for 1900-1979 was obtained from the Steel Statistical Yearbook (published by the International Iron and Steel Institute) and subsequently from a variety of sources including data compiled by the World Steel Association.

Table 1. Note that the demand for copper during 2000-20 was almost certainly supply-constrained. The true demand is likely to have been 4.5% or more.

The main driver of these cycles is the pace of urban (and suburban) construction. When this is proceeding at a rapid pace, global mineral demand is high. When construction activity slows, mineral demand slows with it.

In the 20th century it was North America, Western Europe and, later in the century, the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and Japan which were home to most of the world’s urbanisation and industrial activity. Their economic fortunes drove the century’s four long duration cycles.

1900-1929: Industrialisation and growth

The century began with a 30-year period of high demand driven by the transformation of the USA, Germany, Great Britain, France and other nations from being predominantly agriculture-based, to predominantly urban industrial-based economies. The internal combustion engine and the electric rotor, plus many other inventions, came to the mass market. During this period farms were mechanised and linked to cities via railway networks. The mechanisation of farming and grain transport pushed millions of surplus farmhands to the towns and cities where they found work in the factories and construction sites. Metals were needed as never before. The cities filled up with low-paid factory workers and their families. They were lorded over by a small group of extremely wealthy industrialists, sometimes known (derogatorily) as ‘Robber Barons’.

1929-1938: Slowing demand and The Great Depression

This style of economic development couldn’t last forever. The low-paid workers didn’t have the money to buy the goods being churned out by the ever-growing and increasingly-efficient factory system. So eventually demand for goods began to slow, and when that realisation sank in, it caused panic. The Great Depression was the result. As Table 1 shows during the Great Depression global demand for copper barely grew at all, and the demand for steel actually contracted. To put it into an economic framework: the economies of North America and Western Europe had to shift from one stage of development to the next, and for that to happen the rules governing the economy had to change. In this case the rules which needed changing were those which governed the distribution of income. Put simply, the working class needed a greater share of the money and economic power. The trouble was that the wealthy industrialists weren’t going to let it happen.

1950-1975: The post-war boom

A revolution was needed, and it came in the form of the Second World War. By the end of the war, nations were prepared to introduce social safety nets, higher wages (driven by unions) and a raft of economic incentives to returning soldiers.

The result of this shift was the post-war boom, which is the third cycle shown in the table. With money to spend, the urban workers and their families shifted out of their cramped inner-city apartments and headed for a new life on the city outskirts. There they could buy a house, or at least a larger apartment, and there were grassy areas for the children to run around. They came to be known as ‘sub-urban’ developments, or suburbs. In some nations, more than half the population relocated to the more comfortable lifestyle of the suburbs. Global mineral demand growth returned to high, especially when the original trail-blazing nations of North America and Western Europe were joined by the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc countries, and Japan.

1975-2000: The services revolution

But, once again, this style of economic development couldn’t last forever. By the mid-1970s, many working-class families had become middle class. They had spacious accommodation and all the material goods which went with it. It was plain to see that a new stage of economic growth was needed. This came in the form not of more consumer goods, but of consumer services. Services had always been a big part of the economy. Retail, education, health care, banking and, for the rich, tourism. But the services available to the majority were of a basic, or very expensive, kind. The middle-class families now wanted to change that. A services revolution was needed. For this to happen, some rule changing was needed. That was provided by the Reagan-Thatcher market reforms, and by the arrival of the computer. Over the next ten years, the urbanised and industrialised economies of the world became services economies. It led to renewed economic growth in those nations. It also led to a sharp slowdown in global mineral demand. The reason: unlike the provision of machinery, material goods and urban infrastructure, the provision of services is not a minerals-intensive activity. So it was that last quarter of the 20th century saw a return to low global mineral demand growth. Then along came China.

2000-2020: The China mining boom

China burst onto the global minerals scene in the early 2000s, pushing global mineral demand emphatically back to high. For many, the China boom seemed to come out of the clear blue sky. In fact, China was merely following the path blazed in the early 20th century by the North America, Western Europe, and the other early industrialising countries. It had embarked on this path in the early 1980s by economic reformers who wanted the country to grow wealthy. These reformers set about dismantling the barriers to individual initiative which had been erected by Mao Zedong, namely breaking up the long-standing agricultural communes (for more information on these, see the short Britannica article on the subject).

By the early 1980s China’s farms had returned to single family stewardship. It caused a surge in productivity. In a somewhat later development, the country set itself up as a low-cost global manufacturing hub, and major clusters of factories sprang up all along the coast. The farmers who had been made surplus through the earlier agricultural productivity improvements “migrated” to the cities and found work in these factories. As a result, through the 1980s and 1990s the country transformed into a vibrant economy and by 2000 it was the world’s leading manufacturer-for-export. As a measure of the progress, China’s steel production and consumption had risen markedly in the period to 2010 (see more information in this report by the Reserve Bank of Australia). Those who had noticed this remarkable growth assumed the pace couldn’t continue for much longer. They were wrong about that!

The policy which drove China to dominate the global minerals scene was the decision in 1997 to dismantle the Mao-era policy whereby China’s many large urban corporations were required to provide housing, education, medical care and more to their workforce and their families. By dismantling this safety net, nearly 300 million people would need to fend for themselves. The one small piece of assistance they would be offered was the chance to buy their small, state-owned apartment for a low price.

In a classic case of unintended consequences, this chance to buy their own apartment energised the Chinese housing market and kick-started the biggest construction boom the world has ever seen. The reason: in every coastal Chinese city there was a large population of migrant farmers who had no decent accommodation. Overnight, China’s newly-minted apartment owners became landlords, and the rental income soon allowed them to put down a deposit on a much larger apartment. So it was that the cities became construction sites for high-rise apartment buildings. It was this intense period of high-rise construction which drove the China mining boom.

Of course, and as we have seen with other booms mentioned here, this style of economic development couldn’t last forever. Chinese construction of high-rise buildings and all the infrastructure which goes with it has plateaued. It is now time for the country to move to the next stage of its economic development. However, as we have seen with the examples of the economies of North America and Western Europe, successfully managing this transition is perhaps the most difficult feat for any developing economy. As a result, China looks like it is heading into a prolonged period of weak economic growth. It seems fair to say that it is not going to drive global mineral demand over the next 30 years. So which global region will?

Looking to the future

One possibility of driving future minerals demand is India. After all, I have heard it said that India will be the next China. Yet this is unlikely to be true. There are two reasons for saying this:

- Farms in India are generally not geared towards productivity improvement because they are worked by tenant farmers and the lion’s share of profits go to the absentee landlords. The style of land reform seen in China has not happened in India.

- Even if there was a large surplus farm workforce, there are few manufacturing jobs in the cities for them to go to. This is because, in general, India’s labour and property laws are not favourable to establishing large-scale manufacturing concerns (for more information, see DFAT’s ‘An Indian Economic Strategy to 2035’).

Instead, India’s economic growth is based upon the provision of services and in particular the export of business services. These services sectors are primarily beneficial to the country’s wealthy 20% who are well-educated and English-speaking. The other 80% is not really benefitting from the country’s strong economy. It is for this reason that India’s rate of urbanisation is about 35% (Statista, 2024), the lowest of any global region. Until it has a growing urban population, and a strong manufacturing sector, India will not be a driver of global mineral demand.

What about other global regions? Are there any others which are heading into period of rapid metal-intensive urban construction accompanied by the development of a large manufacturing base and nation-wide infrastructure networks?

Latin America has already likely run its race in this regard. It is already highly urbanised with infrastructure networks already in place, and no likelihood of developing a manufacturing base any larger than it has now. Sub-Saharan Africa is rapidly urbanising, but the development of a large manufacturing base and nationwide infrastructure networks seems a long way off.

The only global region where the right factors exist to drive minerals demand over the next 20 years is South East Asia. However, as a region it is likely too small to drive significant global growth, especially when in all the other regions mineral demand growth is low.

This leads to my conclusion that, for the next 30 years, I have forecast to global mineral demand growth to be at low levels. However, while we will likely not see the same growth as in the post-war or China mining boom periods, there will be modest growth driven by some of the regions mentioned above, as well as demand for new minerals (especially critical minerals) as the world looks to change its global energy mix. Time will tell the level of demand that this will bring, and how it will compare to previous cycles in minerals demand.

About the author

Martin Lynch holds a BE Chemical from The University of Queensland and worked at Rio Tinto from 1990 to 2002, in various operational and corporate roles. He then consulted in the mineral industry for six years. Martin is the author of several books, notably Mining In World History, published in 2004.

References and further reading

Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), 'An India Economic Strategy to 2035', 2024 [online]. Available from: https://www.dfat.gov.au/publications/trade-and-investment/india-economic-strategy/ies/chapter-1.html

Britannica, 2024. ‘Commune – Chinese Agriculture’ [online]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/commune-Chinese-agriculture

Lynch, 2024. ‘Drivers of Global Mineral Demand: 1900–2050’, SEG Discovery, [online]. Available from: https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/segweb/segdiscovery/article-abstract/doi/10.5382/Geo-and-Mining-22/634327/Drivers-of-Global-Mineral-Demand-1900-2050?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Lynch, 2004. Mining in World History, University of Chicago Press.

Reserve Bank of Australia, 2010. ‘China’s Steel Industry’ [online]. Available from: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2010/dec/pdf/bu-1210-3.pdf

Statista, 2024. ‘India: Degree of urbanization from 2012 to 2022’ [online]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271312/urbanization-in-india/